This first appeared in Roar Magazine on September 22, 2021

Radicals have long used food to challenge the status quo. The Nation of Islam’s

navy bean pie was a weapon in its battle against white supremacy.

_ _ _ _ _

by Chuck Morse

Apples fall from trees and berries grow on bushes, but food is not given by nature. It is a construct and, as such, conveys meaning. Although most foods affirm the status quo, there are also foods that register discontent with the dominant social order and hopes for an alternate future. They are part of the foodscape and remind us that dissidents have always contested the food system at the deepest level.

Consider the Nation of Islam’s navy bean pie. This dense, amber-colored dessert embodied a sweeping anti-racist narrative and was a weapon in the group’s battle against white supremacy, evoking the possibility of a cuisine designed to eradicate white terror.

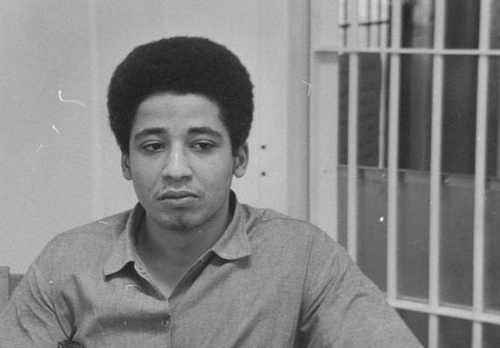

Though diminished today, the Nation of Islam led one of the many challenges to white supremacy that took place in the United States during what some writers have called “the long sixties.” Whereas Martin Luther King Jr. implored white Americans to heed their consciences and join the “beloved community,” the Nation of Islam denounced white depravity and evoked the specter of Black rage. Malcolm X was its best-known member, and his searing indictment of white racism shook the American establishment and echoed globally, but there were tens of thousands of adherents spread out across American cities. The group’s distinctive culture as well as temples, schools, businesses and other institutions bound its devotees into a recognizable, coherent force.

Food was intensely important to the Nation of Islam. Elijah Muhammad, its primary leader and ideologue, released a two-volume book on the topic, How to Eat to Live, and the organization also ran supermarkets, restaurants, bakeries, farms and other food-related businesses. This reflected its commitment to the body as a site upon which to contest white racism and enact Black liberation. While many civil rights advocates focused on changing legislation, the Nation of Islam was a separatist organization and its goals were more inward and corporal. In addition to food, it instructed its members in clothing and hair styles, exercise regimes and reproductive health practices. Its mandates rested on a foundation of explicitly patriarchal, heterosexist norms.

The Nation of Islam embraces a doctrine that bears little resemblance to the Islam practiced by most Muslims in the United States or elsewhere. The group identifies a millennia-long struggle between whites, who are the devil incarnate, and Blacks, who are the chosen ones. It expects this conflict to culminate in “the fall of America,” to cite a book by Elijah Muhammad, followed by Black freedom from white domination. Members used dietary and other body-centered practices to demonstrate their piety as they waited for the coming rupture and to experience moments of redemption in the here and now. For the Nation of Islam, Black empowerment was divine and it could take place on an individual, micro scale as well as on a collective, macro scale.

Elijah Muhammad outlined the culinary dimension of this process in How to Eat to Live, which contains articles that he first published in the group’s newspaper. He argues that Black people should avoid the conventions and foodstuffs of white cuisine, which reflect white people’s “innate wickedness,” and also those of popular Black foodways, often known as “soul food,” which he considered a relic of the “slave diet.” Doing so would allow them to nourish their bodies and affirm their spiritual nobility. He also offered precise instructions on foods to consume and foods to avoid, which ranged from the sensible to the bizarre: he urged members to prioritize fresh fruits and vegetables, to forego all bird except for baby pigeon, and to eat as much cream cheese as possible. Although he did not mention the pie, he repeatedly encouraged the consumption of navy beans.

The navy bean pie is the Nation of Islam’s sole contribution to American food. It is not clear when it first appeared, but it was central to the group’s transformative project. Members filled organizational coffers by selling it to motorists and passersby on streets in cities with active Nation of Islam chapters and at the sect’s restaurants, supermarkets and food stands. Pie sales also expanded the group’s ranks: there are accounts of people who joined the Nation of Islam after forging relationships with members while purchasing the pie. The pie’s ubiquity indicated that the sect had begun to reshape the fabric of urban life and to impact the more intimate realms of taste and diet.

The dish itself embodies the group’s anti-racist outlook in general and Elijah Muhammad’s culinary ideas in particular. The use of a bean filling distinguishes it from white America’s fruit pies, notably the apple pie, the culinary icon of American settler colonialism, and also from the sweet potato pie, a soul food classic. This demarcation unburdens the dessert of culinary legacies that undermine Black greatness. And those who eat it will encounter a tempered sweetness, thanks to use of beans and also the occasional use of brown sugar and whole wheat crusts, which affirms Black temperance and thus piety. Finally, beans evoke the role that grains (and grain storage) played in the rise of cities and thus civilization, tying the pie’s pleasures to narratives of world-building.

Although How to Eat To Live is eclectic and contradictory, persuasive assertions are implicit in the pie. As a dessert, it is principally an affirmation of pleasure. You consume it not to satisfy the demands of hunger, nutrition, or some other necessity, but because it is enjoyable to do so, as an end in its own right. Culinary pleasure, like all pleasure, must be free and uncoerced — it cannot be compelled. Insofar as the Nation of Islam believed that white coercion defines the present epoch, this moment of delight is necessarily an instance of respite from white tyranny. The critique of white food and popular Black foodways written into the pie sets the stage for this embodied experience of liberation, which is literally divine.

And this points toward compelling culinary prospects. If the pie allows for an escape from white oppression, no matter how fleeting, other foods presumably do so as well, and this suggests the possibility of an entire cuisine organized against white supremacy, with its own foods, flavors, textures, cooking practices and eating conventions. How to Eat To Live was too immersed in Nation of Islam maxims to do more than gesture in this direction, but the discourse about pleasure inscribed in the pie provides a more sustainable foundation. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, white radicals produced what Warren Belasco called a “counter-cuisine” in his book on the topic, Appetite for Change. They arrayed their foods against “the system” broadly, whereas the pie signals a cuisine built around opposition to white supremacy specifically.

Communist opponents of white supremacy have been unable to explore this possibility. They have typically regarded culinary matters with indifference and, instead, focused on workplace conflicts and charting a path to power. They have also generally not acknowledged the potential for pre-revolutionary moments of emancipation. For them, cuisine would be important after the revolution; until then, the task is to make it. Even the Black Panther Party’s “Free Breakfast Program,” one of the best-known attempts to link food, Black liberation and communism, treated food as a means to an end. That is, when the Panthers fed poor, Black children, their goal was to demonstrate government neglect and build party support, not to comment on food as such.

Nowadays, it is difficult to find the pie. The Nation of Islam appears to be shrinking and the group’s investment in reactionary, particularly anti-Semitic ideas has justly made it an object of scorn for many. And we have learned things about white supremacy that weaken some of the pie’s premises. When Elijah Muhammad explicated his culinary views, it seemed necessary to re-invent Black food from scratch. As he saw it, slavery had ruptured any connection that African Americans had to their African past and, with it, the threads of a possible counter-tradition in food. History was a void, as signified by the X in Malcolm X’s name, and thus hopes for an alternate future had to be grounded in otherworldly terms. But, in the intervening decades, historians and other scholars have revealed that enslaved Africans often sustained aspects of their own culture, including their culinary culture, despite their captivity. Their legacy can and should be part of any contemporary attempt to create foods that defy white supremacy.

In 1862, Ludwig Feuerbach affirmed a materialist theory of history when he wrote that “man is what he eats.” Of course, Feuerbach was correct, but we also construct what we eat and sometimes our constructs express oppositional convictions. That is true of the Nation of Islam’s navy bean pie. Though embedded in the group’s theology and tied to some of its retrograde impulses, the dish was a tool of mobilization, embodied anti-racist narratives, and conjured expansive culinary possibilities. Its time has passed, but it is a record of contest that demonstrates that the foodscape is richer and more conflicted than we often suppose.